Flywheel training has gained popularity and research support as an efficient and effective training method for a wide range of training goals and backgrounds. Notably, it is known for its ability to challenge the entire range of motion and higher eccentric loading than traditional methods (1,2).

While flywheel training by itself is an efficient and innovative approach with a wide range of benefits (3), adding the precision and power of motorized resistance layers on a whole new dimension to flywheel training! In this blog, I am going to breakdown what Exerfly Motorized Flywheel Training is, why it’s beneficial, and how you can safely and efficiently introduce it and progress it to reach different training goals.

Human muscle fibers can generate greater force when they are being actively lengthened (i.e., eccentric action) compared to other types of muscle actions (4). Most traditional strength training exercises are underloaded during the eccentric phase, since they are limited by strength during the concentric portion of the movement (e.g., up phase of a squat). For this reason, there is value to eccentric overload methods that amplify the loading during the eccentric phase of a movement (5).

Traditional eccentric training methods generally involve the use of weight releasers, spotters to add additional weight during the eccentric phase, or the 2-1 method, where more muscle mass is used during the concentric phase vs the eccentric phase (e.g., lift the weight with two legs, lower it with one). While useful, these methods generally have a few limitations:

Flywheel training helps address these limitations, offering a convenient way to provide eccentric loading across many movement patterns at a variety of speeds and loads. Exerfly Motorized Flywheel Training takes this to the next level, layering precision and higher eccentric loading capabilities onto an already effective training method.

By default, non-motorized flywheel training provides eccentric loading that is ~1:1 with the concentric input. The work performed during the concentric phase accelerates the flywheels, storing kinetic energy which is returned as an eccentric resistance.

While this 1:1 loading is still higher than most strength training methods, researchers and practitioners will often use specific techniques to create eccentric overload for either part or the entire eccentric range of motion (7).

These methods are effective and commonly used in both practice and research, but they have limitations. Delayed braking doesn’t increase the total eccentric load but distributes it to a brief period of intense eccentric effort. It is also difficult to standardize and progress with precision, since the exact braking technique will differ rep to rep and between individuals. Assisted concentrics can increase the total eccentric energy to resist against but has similar challenges in terms of standardization and progressing with precision.

Exerfly Motorized Flywheel training devices address these limitations by combining the mechanical characteristics of flywheels with the versatility and precision of motorized resistance.

Motorized Exerfly devices allow you to add between 1-80% extra kinetic energy to the eccentric phase of each rep of a set. This adds a new dimension to flywheel training, by adding eccentric overload to any movement with precision.

Let’s show a few examples of the motorized boost in action!

For example, the image below shows concentric and eccentric torque values averaged across 8 reps using different percentages of motorized boost (from 0-30%).

Notice that the 0% boost set has similar concentric and eccentric torque values, but there is a clear eccentric overload added as the motorized boost percentage increases.

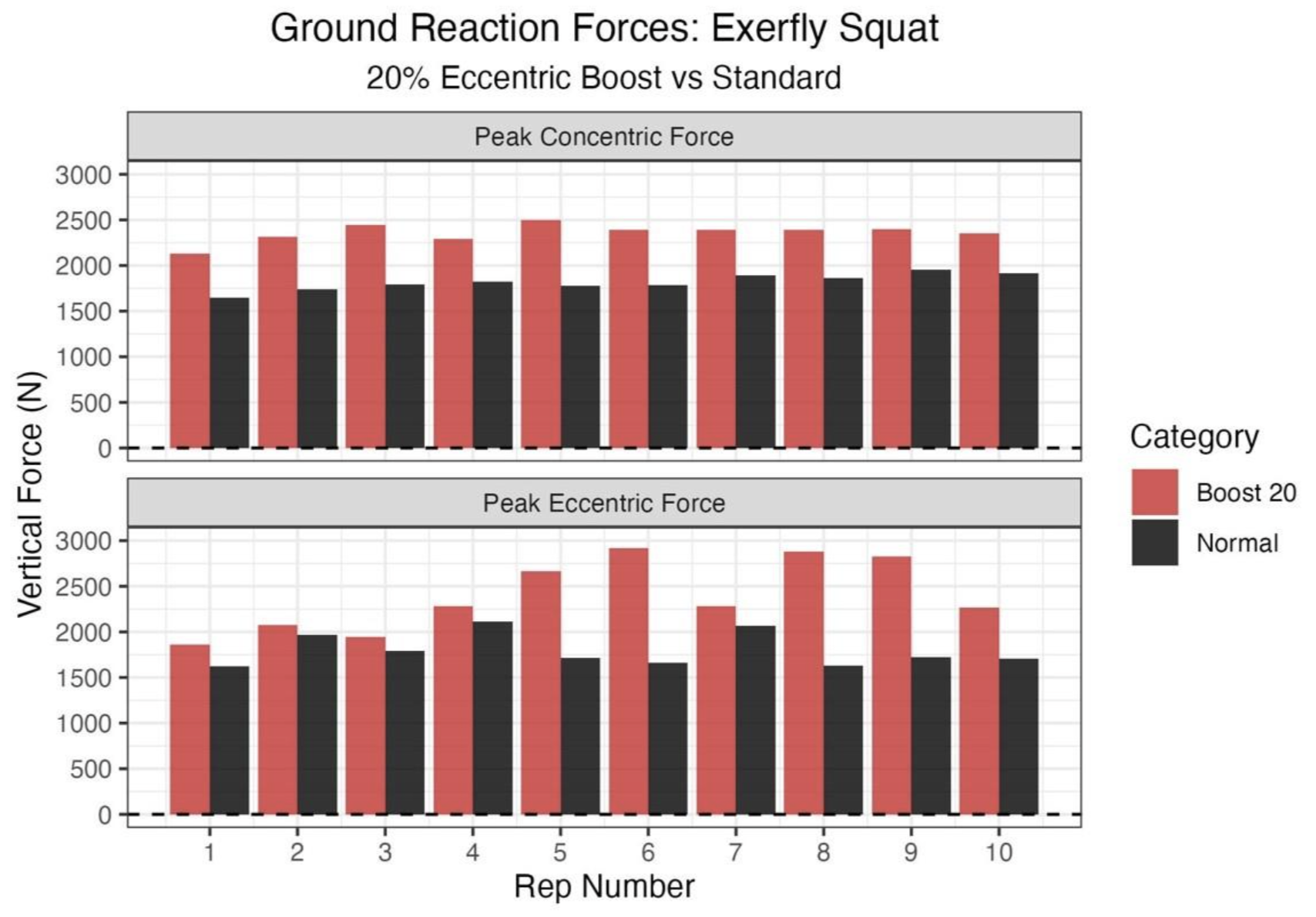

In another case, force plates were mounted on the Exerfly Ultimate and used to measure vertical ground reaction forces during flywheel squats with and without the motorized boost. As expected, the motorized boost increases the peak eccentric forces. But it also increased concentric peak forces as well! This is a common observation when just enough boost is provided with the motor and aligns with research finding that a faster and more forceful eccentric phase can result in higher concentric outputs (8).

Much like its non-motorized counterpart, motorized flywheel training is highly versatile and can be used for many purposes. But here are a few common uses where we’ve seen consistent success.

Flywheel training consistently improves measures of athletic performance and neuromuscular power, likely due to the eccentric loading and ability to develop stretch shortening cycle performance (9–11).

Progressing to motorized flywheel training adds another dimension to this type of training, allowing for eccentric overload to be precisely prescribed and progressed overtime. For example, check out this case study, where motorized flywheel squats were used to drive improvements in countermovement jump peak braking force (+39%), modified reactive strength index (+19%) and jump height (+5%) in just 5 weeks of training.

Importantly, motorized flywheel training can be used to target different adaptations by modifying the loads and speeds. Lower inertial loads can challenge the ability to rapidly brake and re-accelerate in a new direction at high speeds and power outputs. Higher inertial loads with the motor provide a high force eccentric stimulus comparable to heavy accentuated eccentric loading techniques.

Regardless of the load and speed, eccentric overload is provided to each rep, and the loading is based off how much the trainee can put into the rep, addressing common limitations with traditional eccentric overload methods.

For more information on different types of motorized boost strategies, check out this blog.

Flywheel training has also emerged as a promising rehabilitation method, with positive research findings for cases such as patellar tendinopathy (12) and late-stage ACL rehabilitation (13). This benefit is likely due to flywheel training’s eccentric and SSC loading that naturally scales to where the patient is at any given time point, since it is dependent on how much energy put into the concentric phase of each rep.

By introducing motorized flywheel training during late-stage rehab, a progressive dosage of eccentric loading can be provided to develop eccentric capabilities and to target structural and functional adaptations to muscle and connective tissue. This is particularly useful when preparing injured athletes for return to play, as you can progressively increase the eccentric exposure in a controlled manner.

Check out two recent case studies, where motorized flywheel training was used to deliver results within ACL rehabilitation and return to play situations.

We recommend that you are confident and competent with non-motorized flywheel training before introducing the motor. Non-motorized flywheel training is still a highly effective training method, so it is not necessary to jump right to motorized training until you are ready.

Once you are ready, I generally recommend a simple process to introduce and then progress motorized training.

When the motor is engaged, the device sounds and feels slightly differently than when performing training in a purely non-motorized fashion. For this reason, I like to start off with a set or two with a very low boost % (1-2% or just the clutch engaged). This ensures the trainee will be comfortable with how the device feels and sounds during motorized sets, while only being exposed to a very small degree of eccentric overload. This step can be useful for those that want a gradual and conservative introduction to motorized flywheel training, while others may skip right to step 2.

When you’re ready to add some boost, I recommend starting at a low percentage (~5%), and focus on submaximal effort during the initial set. The boost is being added on top of what you put into the movement, so you can start slow, and build up intensity as you gain comfort with this small boost. If the submaximal effort feels comfortable, gradually increase the effort and speed at which you move until you are confident performing high intensity sets with this low % boost.

Once you are comfortable and confident with performing low boost % sets, it’s time to think about how you intend to progress the eccentric resistance over time. Generally, the eccentric loading is dependent on an interplay between:

Depending on your training goals, you can modify each of these three factors across a program. But in most cases, we recommend that only 1-2 is changed at a time to simplify the progression.

For example, one simply strategy is to select an inertial load that aligns with your training goals (e.g., higher inertial load for strength, lower inertial load for speed/power), and then gradually progress concentric velocity and boost % over time. You may spend 2-3 sessions trying to increase your concentric velocity against 5% boost, then increase the boost to 10% and repeat. You could then eventually change the inertial load or exercise and repeat this process.

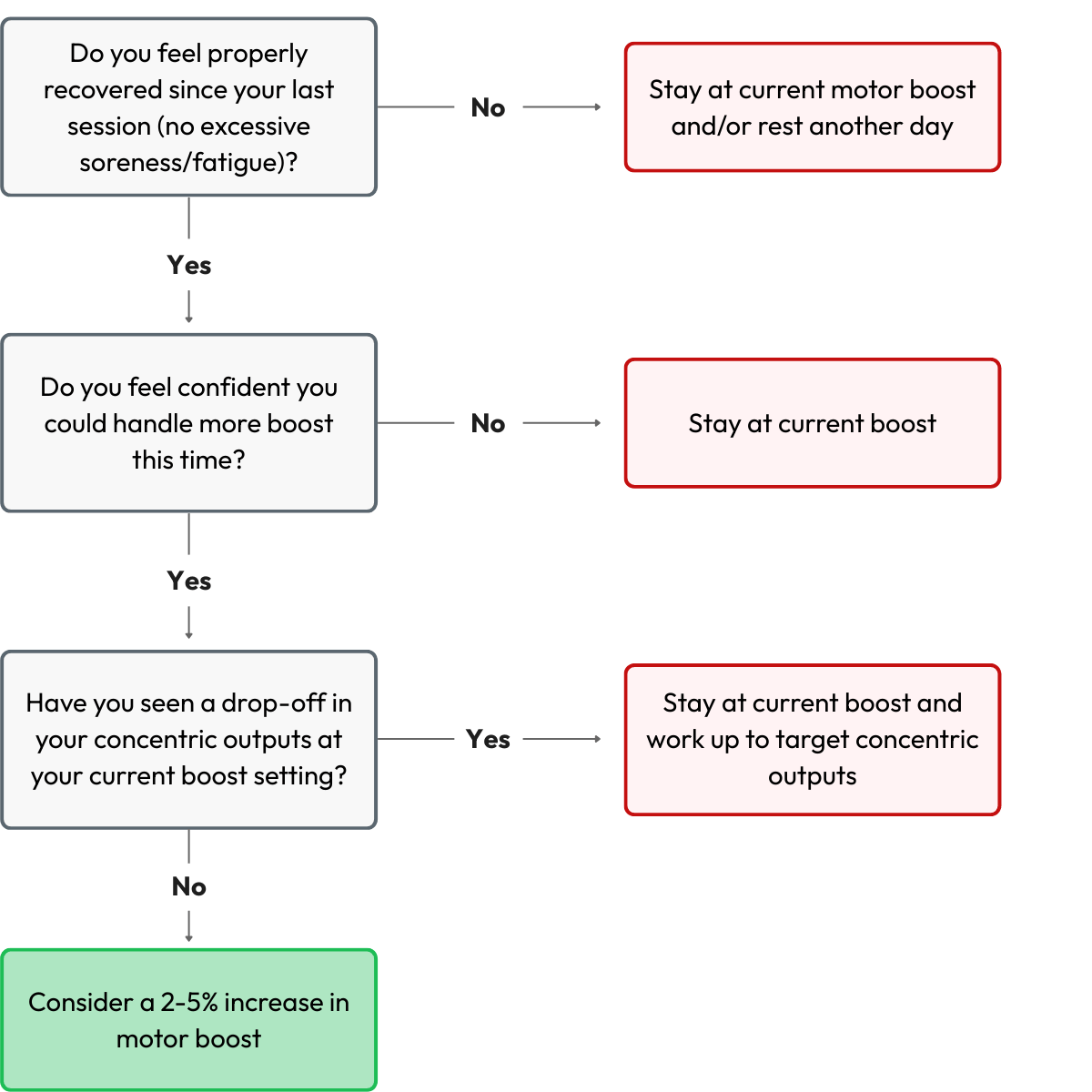

Regardless of your specific progression strategy, it is important to have a plan for how and when to increase the boost %. Figure 1 shows a simple decision tree that can be useful when guiding progressions in motorized boost %. A summary of some key points is listed below.

This is an example of a conservative progression for those that have no motorized flywheel training and want to take a gradual approach towards integrating it. This would occur after you have had some time with non-motorized flywheel training and are ready to progress.

Note: those with a significant training and/or athletic background may be able to progress through Steps 1 and 2 at a faster rate. However, it can be valuable to have a gradual introduction regardless, as proper familiarization to the motor can help even highly trained individuals get the most out of the unique training stimulus.

Exerfly Motorized Flywheel Training provides a unique spin to flywheel training by amplifying the mechanical benefits of flywheels with motorized resistance. This allows for eccentric overload to be provided to each rep across a wide range of movements, loads, and speeds, and the precision to progress by 1% increments. Introducing the motor is also a simple process with a few basic principles and a bit of experience with non-motorized flywheel training.

If you want to deep dive into how motorized flywheel training can be used in your setting, reach out to our team of dedicated flywheel training experts here.

Reference List

1. Norrbrand L, Pozzo M, Tesch PA. Flywheel resistance training calls for greater eccentric muscle activation than weight training. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010 Nov;110(5):997–1005.

2. Tesch PA, Fernandez-Gonzalo R, Lundberg TR. Clinical Applications of Iso-Inertial, Eccentric-Overload (YoYoTM) Resistance Exercise. Front Physiol. 2017 Apr 27;8:241.

3. De Keijzer KL, Gonzalez JR, Beato M. The effect of flywheel training on strength and physical capacities in sporting and healthy populations: An umbrella review. Cortis C, editor. PLoS ONE. 2022 Feb 25;17(2):e0264375.

4. Douglas J, Pearson S, Ross A, McGuigan M. Eccentric Exercise: Physiological Characteristics and Acute Responses. Sports Med. 2017 Apr;47(4):663–75.

5. Douglas J, Pearson S, Ross A, McGuigan M. Chronic Adaptations to Eccentric Training: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017 May;47(5):917–41.

6. Stasinaki AN, Zaras N, Methenitis S, Bogdanis G, Terzis G. Rate of Force Development and Muscle Architecture after Fast and Slow Velocity Eccentric Training. Sports. 2019 Feb 14;7(2):41.

7. Martínez-Hernández D. Flywheel Eccentric Training: How to Effectively Generate Eccentric Overload. Strength & Conditioning Journal. 2024 Apr;46(2):234–50.

8. Hernández-Davó JL, Sabido R, Omar-García M, Boullosa D. Why Should Athletes Brake Fast? Influence of Eccentric Velocity on Concentric Performance During Countermovement Jumps at Different Loads. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2024 Apr 1;19(4):375–82.

9. Chaabene H, Markov A, Prieske O, Moran J, Behrens M, Negra Y, et al. Effect of Flywheel versus Traditional Resistance Training on Change of Direction Performance in Male Athletes: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. IJERPH. 2022 June 9;19(12):7061.

10. Shimizu T, Tsuchiya Y, Tsuji K, Ueda H, Izumi S, Ochi E. Flywheel Resistance Training Improves Jump Performance in Athletes and Non-Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int J Sport Health Sci. 2024;22(0):61–75.

11. Shimizu T, Tsuchiya Y, Ueda H, Izumi S, Ochi E. Eight‐Week Flywheel Training Enhances Jump Performance and Stretch‐Shortening Cycle Function in Collegiate Basketball Players. European Journal of Sport Science. 2025 Feb;25(2):e12257.

12. Burton I, McCormack A. Inertial Flywheel Resistance Training in Tendinopathy Rehabilitation: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Sept 3];17(5). Available from: https://ijspt.scholasticahq.com/article/36437-inertial-flywheel-resistance-training-in-tendinopathy-rehabilitation-a-scoping-review

13. Stojanović MDM, Andrić N, Mikić M, Vukosav N, Vukosav B, Zolog-Șchiopea DN, et al. Effects of Eccentric-Oriented Strength Training on Return to Sport Criteria in Late-Stage Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL)-Reconstructed Professional Team Sport Players. Medicina. 2023 June 8;59(6):1111.

Get a monthly update with new research, blogs, and exclusive offers.